Рейтинг: 4.0/5.0 (1847 проголосовавших)

Рейтинг: 4.0/5.0 (1847 проголосовавших)Категория: Windows: Языки

Особенности программы:

* Легкость, простота, скорость

Эргономичность интерфейса программы: на экране нет лишних элементов, усложняющих восприятие информации, только то, что следует воспринять и запомнить. Наличие только необходимой информации приводит к ее легкому восприятию, быстроте обучения, увеличивая эффективность

* Глубокое запоминание, высокая эффективность

Используются упражнения разной направленности (Карточка, Мозаика, Выбор перевода, Угадать перевод, Выбор слова, Написание), основанные на особенностях работы ассоциативной памяти человеческого мозга

* Адаптация под Ваши способности

Бальная система оценки, штраф за неверный ответ позволяют адаптировать процесс изучения слов под Ваши способности к запоминанию

* Cистема повторений

Универсальная система повторений, гибко реализует методику периодических повторений, что позволяет надежно запомнить изученные ранее слова и фразы

* Гибкость обучения

LearnWords развивается как инструментарий для эффективного изучения слов. Вы можете составить свою схему обучения, распределив упражнения по уровням обучения (Настройка\Уровни).

* Богатая функциональность

o Транскрипция слов обеспечивает правильность прочтения незнакомых слов;

o Произношение (озвучивание слов) поможет восприятию слова на слух, развитию навыка устной речи;

o Настройки позволяют настроить работу программы "под себя", изменить внешний вид упражнений;

o Статистика обучения показывает количество и степень (в процентах) изученного материала;

o Создание словарей: составление личных словарей, редактирование существующих с помощью встроенного "Редактора слов". Все типы словарей можно создавать и редактировать с помощью многофункционального, бесплатного редактора для настольного компьютера LearnWords Editor!

o Дополнительные функции: поддержка виртуальной клавиатуры, случайный выбор слов блока, изучение слов выбранной категории, случайный выбор слов блока, обмен местами полей слово и перевод, многое другое;

* Большое количество словарей

Десятки бесплатных словарей доступны для скачивания со страницы Словари.

Большинство словарей упорядочено по частоте употребления в языке, активная лексика, тематические, фразы и грамматика.[/I]

* Свыше двадцати языков

английский, немецкий, французский, испанский, итальянский, арабский, иврит, греческий, финский, чешский, болгарский, латышский, датский, голландский, эстонский, венгерский, польский, норвежский, шведский и другие

Стоимость регистрации 580 рублей.

Пока на Маркете программы нет.

Наибольшая русскоязычная база с чит кодами, трейнерами и прохождениями для компьютерных игр. Все чит коды переведены и проверены лично нами. Количество игр представленных в текущей версии - 11161.

Эта программа представляет собой бесплатный аналог Adobe Photoshop. Она точно также включает в себя множество инструментов для работы с растровой графикой, и даже имеет ряд инструментов для векторной графики. GIMP это полноценная замена Photoshop.

Мощная и бесплатная антивирусная программа, которая защитить ваш компьютер от всяческих угроз, включая вирусы, трояны, и т.д. AVG Anti-Virus Free также защитить вас в Интернете от потенциально опасных веб-сайтов и других видов угроз.

LearnWords Windows версия 6.0 + LearnWords Editor 5.01

Год/Дата Выпуска. 2012

Версия. 6.0

Разработчик. LearnWords Software

Разрядность. 32bit+64bit

Совместимость с Vista. полная

Совместимость с Windows 7. полная

Язык интерфейса. Английский + Русский

Таблэтка. Присутствует

Системные требования. Windows (7/Vista/XP/2000/Me/98)

Описание. Изучение английских слов, французского, испанского, итальянского, китайского и других языков. С LearnWords изучение иностранного языка максимально эффективно, просто и увлекательно!

Обучение состоит в выполнении шести основных упражнений для выбранного из словаря блока слов. От первого знакомства со словом (Карточка), переход к более сложному упражнению, позволяющему "отгадать" правильность перевода, очищая "игровой стакан" (Мозаика); далее закрепляется ассоциация "слово-перевод" (Выбор перевода), проверяется упражнением Угадать перевод, в котором перевод уже требуется вспомнить самостоятельно; более сложную ассоциацию "перевод-слово" вырабатывает упражнение Выбор слова, и, наконец, упражнение Написание обеспечивает запоминание правильного написания слова. Поддержка звуковых файлов с произношением слов и синтеза речи, создает еще одну ассоциацию восприятия слова на слух, что поможет Вам понять иностранную речь и выработать правильное произношение.

последовательное выполнение всех упражнений для каждого слова вырабатывает необходимые, устойчивые ассоциативные связи;

игровая составляющая обеспечивает легкость изучения;

система баллов и уровней обеспечивает гарантию уверенного запоминания.

Слова мало выучить, необходимо их надежно и надолго запомнить, отправить на хранение в долговременную память. Решить эту задачу позволяет универсальная система повторений. Система реализует график повторений по Эббингаузу, что позволяет запомнить любую, даже бессвязную информацию.

Доп. информация. словари выбираются по вкусу и скачиваются с http://www.learnwords.ru/database.html

В пакете присутствует инструмент редактирования словарей и создания личных словарей.

Важно. Возможно это только у меня, но нортон антивирус съел крякнутые файлы, поэтому, возможны приключения.

How many Russian words do you know? 1,500 words are required to smatter of the language. 15,000 words provide good command of the language. It really takes an eternity to learn so many words but you could help it.

Here's what you should do to organize the process of learning foreign words correctly.

General Principles Firstly, there are some general principles:Now that you know the general principles look at some methods of learning new words.

Traditional methodThis method is the simplest but least effective. Write out 20 to 25 new words in a column. Put foreign words on the left and their translation to your native language on the right. Focus on memorizing the words for good. It is important to concentrate your attention.

Now read the whole list carefully line by line. Then have a ten minute break doing something else. After that cover the left column and try to recall the script and pronunciation of all the words from the list. Skip the word if you can't recall it for long.

Have another five minute break. Then recall all the words again. Try to concentrate your attention on the words you could not recall the first time.

Go on reviewing until you are able to recollect the translation of all the words from your list (however put the learning off if you feel tired). Have a rest now. It is needed for your brain to regain its strength.

Review your word list in 7-10 hours after you've learned them. Then review it each 24 hours. The total of four revisions is required and enough.

Note: It is good to put new words on 0,8 x 1,2 inch cards with Russian words on one side and their translation on the other side.

Creative methodThis method is based on constructing bright, colorful, moving pictures in your mind. Firstly, find a word from your native language that would sound similar to the Russian word you want to remember. Then write down the Russian word, consonant word from your native language, and translation. Look at the example:

снег (snyek) -- snack -- snow

Now think of a picture that would combine the images of snack and snow. The picture should be unusual, illogical and include some motion.

Well, imagine you take a snack from a table and put it into a freezer. The freezer starts working like hell and the snack is being coated with white and shining snow before your very eyes. That's it.

Thanks to that picture the Russian word "снег" will make you recollect the English word 'snow' (and vise versa) every time you encounter it.

Pay special attention to the process of movement because static pictures are quick to escape your remembrance. Do not learn more than 25 words at a time.

Abstract nouns, adjectives, adverbs and verbs will be a bit harder to memorize. In this case you should prolong the chain of words. Suppose you want to remember the word "упрямый" (obstinant). Let's construct the following chain of words:

"упрямство" (yoopryahm stvah) --

you pram stuff -- obstinacy -- obstinate as a mule

Now imagine a narrow passage. You are pushing forward a pram full of milk. A mule is on you way, its head tightly pressed to your pram. It is trying to move forward and prevents you from pushing your pram obstinately. This picture will work great.

Passive perception methodRecord 40 to 50 new Russian words with their translations. Listen to the recording as many times as possible at normal volume level. You don't need to pay any attention to what you hear. After a great deal of playbacks the words will be memorized of their own accord.

Motor-muscular methodHere you should feel and manipulate the subject designated by the word you want to remember. Thus, if you are going to learn the word "свеча" (a candle), take a candle, touch, smell, explore it and finally put a match to it. Or if you want to remember the word "ласкать" (to caress), caress your cat. It is necessary to pronounce the words in Russian while repeating your actions several times.

Got questions?Ask them in the Russian Questions and Answers — a place for students, teachers and native Russian speakers to discuss Russian grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation, and other aspects of the Russian language.

A few days back, we had taken a look at a few resources which helped us with slangs and day to day jargons. Street language sounds hep and helps us to keep up with the times. But it also limits our vocabulary. There’s a word in the English language for every instance, provided we care enough to adopt and use it.

A few days back, we had taken a look at a few resources which helped us with slangs and day to day jargons. Street language sounds hep and helps us to keep up with the times. But it also limits our vocabulary. There’s a word in the English language for every instance, provided we care enough to adopt and use it.

There are only two ways to learn new words – read and use.

Think about it, a word a day translates to nearly 300 words over the course of a year; and many more over a lifetime. An expanded vocabulary not only helps to ace tests like SAT/ACT, but also opens up the language that we speak every day. Read a great speech and see how it moves you. Its oration backed up by a great vocabulary.

So, let’s take it a word at a time and seek the help of these ten websites that teach us new words in different ways.

Wordsmith.org is one of the better examples of a stripped down, plain Jane website that hides a lot of usefulness behind its looks. If you have to use just one of the services listed, opt for the daily newsletter. A word a day delivered to your inbox. The screenshot shows how a single word is covered in all its shades.

A single word each day is illustrated with a cartoon. If you have a visual sort of memory, you won’t have any trouble picking up quite a few words over the course of a month, and learning to use them as they are meant to be. The blog is expecting a rebirth in a new avatar soon.

From cartoons to video, visual learning is the new mantra and it seems it’s no different for dictionaries. Wordia functions like a normal dictionary but instead of text definitions, you get videos explaining the usage of a word. The video explanations seem more thorough and easier to grasp than the textual definition. Everyday you can test yourself with Vocability. the Wordia game.

Vocab VitaminsThe vocabulary learning tool gives you doses of “?verbal supplements’ daily in the mail and also on the site. Word of the day is also arranged around a central theme. For instance, the word “?doldrums’ belongs to the week’s theme – “?How’s the weather?

[NO LONGER WORKS] Save The WordsSavethewords.org is a beautifully constructed website that endeavors to focus attention on the lesser known words in the English language. The Oxford Dictionaries site seeks to save these words from going into a state of non-usage and non-existence. The surefire way to do that is to “?adopt’ a word and use it in daily conversation. The site helps out by sending out word-a-day mailers to those of us who are passionate about words and their meanings. (See [NO LONGER WORKS] Directory mention)

Wordnik.com covers meanings through example sentences to audio pronunciations. Like a lot of online word tools, it aims to go beyond the scope of traditional dictionaries by taking a 360 degree look at a word, the word-of-the-day page and mailer is a shortcut to that process. Wordnik makes it easier to grasp new words by also providing instances of related words and images to describe context.

[NO LONGER WORKS] PhraysPhrays.com takes a competitive approach to making you learn a word every day. Each day, a word is displayed with its meaning on the site and you have to write a sentence using the word. The sentence with the most user votes is the winner. You can also see the creative Zen of the previous winners that’s also on display in the archives. (See Directory mention)

WordThink.com does not believe in learning new words just its own sake. It bunks the more complicated words and goes in for words that you might use in your daily conversations. You might not find a word like eleemosynary here, but the site might show you benevolent instead. WordThink sources the words from media and news.

VocabsushiIf you are hell bent on acing college tests like ACT, SAT, GMAT, GRE etc, try out Vocabsushi and its bite-size learning method. You can test where you stand with a 20-question Vocabsushi demo quiz right on the front page. Pick a test from the dropdown and have a go at it. If you don’t fare that well, it’s time to dive into Vocabsushi more seriously. Vocabsushi uses thousands of sentences from contemporary news sources that show how a word is used in the real world. The actual words are taken from standardized tests that students have to take. Vocabsushi is a superbly designed site with tools like MP3 clips (for pronunciations), word games, offline quizzes in PDF, etc. (See Directory mention)

BBC Learning EnglishThere’s no end to learning new words and adding them to your vocabulary. Words aren’t meant to make you a dictionary on two legs, but to in fact make your conversations simpler. Do you agree?

How many words do you need to know in English? This is a very common question and it varies depending on your goal. Because TalkEnglish.com focuses on speaking, the vocabulary presented in this section will be the most commonly used words in speaking.

GOOD NEWS - If your goal is to speak English fluently, you are not required to study 10,000 words. 2,000 is enough to get you started.

Here is another list of things to consider before studying vocabulary

If you had to choose the first 2,000 words to learn, the list below is very accurate. The number next to the link is the actual number.

Out of the 2265 words in the list, a total of 1867 word families were present.

The following is broken down by type of words. All the words in the following lists are in the list of 2000 words. The sum is greater than 2,000 because many words can be both a noun and a verb.

Finally, before you start studying vocabulary, keep in mind that you will need to learn a lot more than 2,000 words. However, studying the right 2,000 words in the proper depth will help you to become fluent in English much faster.

A word list tehnique is in its most common form a list of words in a target language with one translation of each word into another language, here called the base language. However you can use short idiomatic word combinations instead of single words, or you can give more than one translation into the base language, and it will still be a word list. You can also add short morphological annotations, but there isn't room for examples or long comments in a typical word list. Lists of complete sentences with translations are not word lists.

There are also word lists with just one language (frequency lists) or with more than two languages. The so called Swadesh lists (named after Morris Swadesh) contain corresponding lexical items from a number of languages, typical 100 or 200 items chosen among the most common words. Both these lists can be valuable for a language learner who wants to make sure that s(he) covers the basic vocabulary of a target language.

Dictionaries can be seen as sophisticated word lists, where the target items (lexemes) are put in alphabetical order, and where the semantic span of each lexeme is illustrated through the use of multiple translations, explanations and examples, sometimes even quotes. In addition good dictionaries give morphological information about both the target language and the base language words. However the amount of information in dictionaries varies, and the most basic pocket dictionaries are hardly more than alphabetized word lists.

Using word listsThe most conspicuous use of word lists is the one in text books for language learners, where the new words in each lesson are summarized with their translations. However they are also an important element of language guides used by tourists who don't intend to learn the language of their destination, but who need to communicate with local people. In both cases the need to cover all possible meanings of each foreign word is minimized because only some of them are relevant in the context, - in contrast, a dictionary should ideally cover as much ground as possible because the context is unknown.

Using word lists outside those situations has been frowned upon for several reasons which will be discussed below. However they can be a valuable tool in the acquisition of vocabulary, together with other systems such as flash cards. The method that is described below was introduced by Iversen in the how-to-learn-all-languages forum as a refinement of the simple word lists, and it was invented because he found that simple word lists weren't effective when used in isolation (except for recuperation of half forgotten vocabulary).

MethodologyOne basic tenet of the method is that words shouldn't be learnt one by one, but in blocks of 5-7 words. The reason is that being able to stop thinking about a word and yet being able to retrieve it later is an essential part of learning it, and therefore it should be trained already while learning the word in the first place. Normally people will learn a word and its translation by repetition: cheval horse, cheval horse, cheval horse. (or horse cheval cheval cheval cheval. ), or maybe they will try to use puns or visual imagery to remember it. These techniques are still the ones to use with each word pair, but the new thing is the requirement that you learn a whole block of words in one go. The number seven has been chosen because most people have an immediate memory span of this size. However with a new language where you have problems even to pronounce the words or with very complicated words you may have to settle for 5 or even 4 words, - but not less than that.

Another basic tenet is that you should learn the target language words with their translations first, but immediately after you should practice the opposite connection: from base language to target language. And a third important tenet is that you MUST do at least one repetition round later, preferably more than one. Without this repetition your chances of keeping the words in your long time memory will be dramatically reduced.

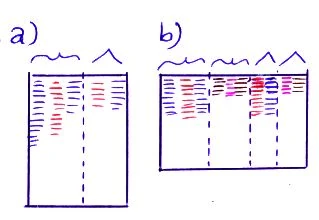

This is the practical method: Take a sheet of paper and fold it once (a normal sheet of paper is too cumbersome, and besides you need too many words to fill it out). If you have a very small handwriting you can draw lines to divide it as shown as b) below, otherwise divide it into two columns as shown under a). The narrow columns are for repetition (see below). Lefthanders may invert the order of the columns if that feels more comfortable. Blue: target language, red: base language. Curvy top: original column, triangle top: repetition column

Now take 5-7 words from your source and write them under each other in the leftmost third of the left column. Don't write their translations yet, but use any method in your book to memorize the meanings of these 5-7 words (repetition, associations), - if you want to scribble something then use a separate sheet. Only write the translations when you are confident that you can write translations for all the words in one go. And use a different color for the translations because this will make it easier to take a selective glance at your lists later. If you do fail one item then look it up in your source, but wait as long as possible to write it down - postponement is part of the process that forces your brain to move the word into longterm memory.

OK, now study these words and make sure that you remember all the target language words that correspond to the translations. When you are confident that you know the original target words for every single translation you cover the target column and 'reconstruct' its content from the translations. Once again: If you do fail one item then look it up in your source, but wait as long as possible to write it down (for instance you could do it together with the next block) - the postponement is your guarantee that you can recall the word instead of just keeping it in your mind. So now you have three columns inside the leftmost column, and you are ready to proceed to the next block of 5-7 words. Continue this process until the column is full.

There isn't room for long expressions, but you can of course choose short word combinations instead of single words. It may also be worth adding a few morphological annotations, but this will vary with the language. For instance you could put a marker for femininum or neuter at the relevant nouns in a German wordlist, - but leave out masculinum because most nouns are masculine and you need only to mark those that aren't. Likewise it might be a good idea to indicate the consonant changes used for making aorists in Modern Greek, but only when they aren't self evident. In Russian you should always try to learn both the imperfective and the corresponding perfective verb while you are at it, and so forth. You can't and you shouldn't try to cram everything into your word lists, but try to find out what is really necessary and skip the details and the obvious.

SourcesYou can get your words from several kinds of sources. When you are a newbie you will probably have to look up many words in anything you read in the target language. If you write down the words you look up then these informal notes could be an excellent source, - even more so because you have a context here, and it would be a reasonable assumption that words you already have met in your reading materials stand a good chance of turning up again and again in other texts. Later, when you already have learned a lot of words, you can try to use dictionaries as a source. This is not advisable for newbies because most of the unknown words for them just are meaningless noise, but when you already know part of the vocabulary of the language (and have seen, but forgotten countless words) chances are that even new unknown words somehow strike a chord in you, and then it will be much easier to remember them. You can use both target language dictionaries and base language dictionaries, - or best: do both types and find out what functions best for you.

RepetitionAs mentioned above repetition is an indispensable part of the process, and it should be done the next day (preferably) or just later on the same day. The repetition can of course be done in several ways, but in the two layouts above there are special columns for this purpose, - it is easier to keep track of your repetitions when they are on the same sheets as the original wordlists. However these column are only subdivided in two parts, one for the words in the base language, the other for the target language words. So you copy 5-7 base language words from the original wordlist, cover the source area and try to remember the original target language words. If you can't then feel free to peek, but - as usual - don't write anything before you can write all 5-7 words in one go. An example with Latin and English words:

The combined layout was the one I developed when I had used three-column wordlists for a year or so and found out that I had a tendency to postpone the revision - having it on the same sheet as the original list would show me exactly how far I had done the revision, and I would only have to rummage around with one sheet. And for wordlists based on dictionaries or premade wordlists (for instance from grammars) it is still the best layout. But I have since come to the conclusion that it isn't the most logical way to do the revision for wordlists based on texts, especially those which I had studied intensively and maybe even copied by hand. Here the smart way to work is to go back to the original text (or the copy) and read it slowly and attentively while asking myself if I know and really understood each and every word. I had put a number of words on a wordlist because I didn't know them so if I now could understand them without problems in the context then I would clearly have learnt something - and I would also get the satisfaction of being able to read at least one text freely in the target language. If a certain word still didn't appear as crystal clear to me then it would just have to go into my next wordlist for that language. So now I have dropped the repetition columns for text based wordlists.

Then what about later repetitions? After all, flash cards, anki and goldlists all operate with later repetitions. Personally I believe more in doing a proper job in the first round (where there actually are several 'micro-repetitions' involved), but it may still be worth once in a while to peruse an old wordlist. My advice here is: write the foreign words down, but only with translation if you feel that a certain word isn't absolutely well-known - which will happen with time no matter which technique you have used. The format doesn't matter, but writing is better than just reading - and paradoxically it will also feel more relaxed because you don't have to concentrate as hard when you have something concrete like pencil and paper to work with.

Memorization techniques and annotationsWhen you write the words in a word list you shouldn't aim for completeness. If a word has many meanings then you may choose 1 or 2 among them, but filling up the base language column with all sorts of special meanings is not only unaesthetic, but it will also hinder your memorization. Learn the core meaning(s), then the rest are usually derived from it and you can deal with them later. Any technique that you would use to remember one word is of course valid: if you have a 'funny association' then OK (but take care that you don't spend all your time inventing such associations), images are also OK and associations to other words in the same or other languages are OK. The essential thing in the kind of wordlist I propose here is not how you do the actual memorization, but that you are forced to do it several times in a row because of the use of groups, and that you train the recall mechanism both ways.

It will sometimes be a good idea to include simple morphological or syntactical indications. For instance English preposition with verbs, because you cannot predict them. Such combinations therefore should be learnt as unities. For the same reason I personally always learn Russian verbs in pairs, i.e. an imperfective and the corresponding perfective verb(s) together. With strong verbs in Germanic languages you can indicate the past tense vowel (strong verbs change this), and likewise you can indicate what the aorist of Modern Greek verbs look like - mostly one consonant is enough. There is one little trick you should notice: if you take a case like gender in German, then you have to learn it with each noun because the rules are complicated and there are too many exceptions. However most nouns are masculine, so it is enough to mark the gender at those that are feminine or neuter, preferably with a graphical sign (as usual Venus for femininum, and I use a circle with an X over to mark the neutrum). This is a general rule: don't mark things that are obvious.

Arguments against using word listsFinally: which are the arguments against the methodical use of word lists in vocabulary learning?

One argument has been that languages are essentially idiomatic, and that learning single words therefore is worthless if not downright detrimental. There is a number of very common words in any language where word lists aren't the best method because they have too many grammatical and idiomatic quirks, - however you will meet these words so often that you will learn them even without the help of word lists. On the other hand most words have a welldefined semantic core use (or a limited number of well defined meanings), and for these words the word list method is a fast and reliable way to learn the basics.

Another argument is that some people need a context to remember words. For these people the solution is to use word lists based on words culled from the books they read.

A third argument is that the use of translations should be avoided at any costs because you should avoid coming in the situation that you formulate all your thoughts in your native language and then translate them into the target language. But this argument is erroneous: the more words you know the smaller the risk that your attempts to think and talk in the target language fail so that you are forced to think in your native language.

A fourth argument: word lists is a method based entirely on written materials, and many people need to hear words to remember them. This problem is more difficult to solve, - you could in principle have lists where the target words were given entirely as sounds (or as sounds with undertexts), but you would have serious problems finding such lists or making them yourself. But listening to isolated spoken words is in itself a dubious procedure because you hear an artificial pronunciation and not the one used in ordinary speech. However the same argument could be raised against any other use of written sources, except maybe listening-reading techniques.

A fifth argument: there is a motivational problem insofar that many people prefer learning languages in a social context, and working with word lists is normally a solitary occupation. It might be possible to invent a game between several persons based upon word lists, but it would not be more attractive or effective than the forced dialogs and drills used in normal language teaching.

Finally an example based on Dutch-Danish and Spanish-Danish (based on an older layout without repetition columns):

AlternativesOf course there are alternatives to wordlists: the most extreme is the exclusive use of graded texts as the most vehement adherents of the natural method propose. I don't understand their motives, but respect their bravery. However I do understand the unorganized use of dictionaries plus genuine texts, but frankly I think there is room for improvement in that method.

Finally, there are well-structured alternatives like paperbased flashcards and electronic versions of these, all based on the notion of 'spaced repetition': Anki, Supermemo. However I can't give advice concerning these systems because I haven't tried them myself.

Posted on July 7, 2014

IntroductionIn the last few years, deep neural networks have dominated pattern recognition. They blew the previous state of the art out of the water for many computer vision tasks. Voice recognition is also moving that way.

But despite the results, we have to wonder… why do they work so well?

This post reviews some extremely remarkable results in applying deep neural networks to natural language processing (NLP). In doing so, I hope to make accessible one promising answer as to why deep neural networks work. I think it’s a very elegant perspective.

One Hidden Layer Neural NetworksA neural network with a hidden layer has universality: given enough hidden units, it can approximate any function. This is a frequently quoted – and even more frequently, misunderstood and applied – theorem.

It’s true, essentially, because the hidden layer can be used as a lookup table.

For simplicity, let’s consider a perceptron network. A perceptron is a very simple neuron that fires if it exceeds a certain threshold and doesn’t fire if it doesn’t reach that threshold. A perceptron network gets binary (0 and 1) inputs and gives binary outputs.

Note that there are only a finite number of possible inputs. For each possible input, we can construct a neuron in the hidden layer that fires for that input, 1 and only on that specific input. Then we can use the connections between that neuron and the output neurons to control the output in that specific case. 2

And so, it’s true that one hidden layer neural networks are universal. But there isn’t anything particularly impressive or exciting about that. Saying that your model can do the same thing as a lookup table isn’t a very strong argument for it. It just means it isn’t impossible for your model to do the task.

Universality means that a network can fit to any training data you give it. It doesn’t mean that it will interpolate to new data points in a reasonable way.

No, universality isn’t an explanation for why neural networks work so well. The real reason seems to be something much more subtle… And, to understand it, we’ll first need to understand some concrete results.

Word EmbeddingsI’d like to start by tracing a particularly interesting strand of deep learning research: word embeddings. In my personal opinion, word embeddings are one of the most exciting area of research in deep learning at the moment, although they were originally introduced by Bengio, et al. more than a decade ago. 3 Beyond that, I think they are one of the best places to gain intuition about why deep learning is so effective.

A word embedding \(W: \mathrm

\[W(``\text

\[W(``\text

(Typically, the function is a lookup table, parameterized by a matrix, \(\theta\). with a row for each word: \(W_\theta(w_n) = \theta_n\) .)

\(W\) is initialized to have random vectors for each word. It learns to have meaningful vectors in order to perform some task.

For example, one task we might train a network for is predicting whether a 5-gram (sequence of five words) is ‘valid.’ We can easily get lots of 5-grams from Wikipedia (eg. “cat sat on the mat”) and then ‘break’ half of them by switching a word with a random word (eg. “cat sat song the mat”), since that will almost certainly make our 5-gram nonsensical.

Modular Network to determine if a 5-gram is ‘valid’ (From Bottou (2011) )

The model we train will run each word in the 5-gram through \(W\) to get a vector representing it and feed those into another ‘module’ called \(R\) which tries to predict if the 5-gram is ‘valid’ or ‘broken.’ Then, we’d like:

W(``\text

W(``\text

W(``\text

\[R(W(``\text

W(``\text

W(``\text

W(``\text

W(``\text

In order to predict these values accurately, the network needs to learn good parameters for both \(W\) and \(R\) .

Now, this task isn’t terribly interesting. Maybe it could be helpful in detecting grammatical errors in text or something. But what is extremely interesting is \(W\) .

(In fact, to us, the entire point of the task is to learn \(W\). We could have done several other tasks – another common one is predicting the next word in the sentence. But we don’t really care. In the remainder of this section we will talk about many word embedding results and won’t distinguish between different approaches.)

One thing we can do to get a feel for the word embedding space is to visualize them with t-SNE. a sophisticated technique for visualizing high-dimensional data.

t-SNE visualizations of word embeddings. Left: Number Region; Right: Jobs Region. From Turian et al. (2010). see complete image.

This kind of ‘map’ of words makes a lot of intuitive sense to us. Similar words are close together. Another way to get at this is to look at which words are closest in the embedding to a given word. Again, the words tend to be quite similar.

What words have embeddings closest to a given word? From Collobert et al. (2011)

It seems natural for a network to make words with similar meanings have similar vectors. If you switch a word for a synonym (eg. “a few people sing well” \(\to\) “a couple people sing well”), the validity of the sentence doesn’t change. While, from a naive perspective, the input sentence has changed a lot, if \(W\) maps synonyms (like “few” and “couple”) close together, from \(R\) ’s perspective little changes.

This is very powerful. The number of possible 5-grams is massive and we have a comparatively small number of data points to try to learn from. Similar words being close together allows us to generalize from one sentence to a class of similar sentences. This doesn’t just mean switching a word for a synonym, but also switching a word for a word in a similar class (eg. “the wall is blue” \(\to\) “the wall is red ”). Further, we can change multiple words (eg. “the wall is blue” \(\to\) “the ceiling is red ”). The impact of this is exponential with respect to the number of words. 4

So, clearly this is a very useful thing for \(W\) to do. But how does it learn to do this? It seems quite likely that there are lots of situations where it has seen a sentence like “the wall is blue” and know that it is valid before it sees a sentence like “the wall is red”. As such, shifting “red” a bit closer to “blue” makes the network perform better.

We still need to see examples of every word being used, but the analogies allow us to generalize to new combinations of words. You’ve seen all the words that you understand before, but you haven’t seen all the sentences that you understand before. So too with neural networks.

From Mikolov et al. (2013a)

Word embeddings exhibit an even more remarkable property: analogies between words seem to be encoded in the difference vectors between words. For example, there seems to be a constant male-female difference vector:

\[W(``\text

W(``\text

W(``\text

This may not seem too surprising. After all, gender pronouns mean that switching a word can make a sentence grammatically incorrect. You write, “she is the aunt” but “he is the uncle.” Similarly, “he is the King” but “she is the Queen.” If one sees “she is the uncle ,” the most likely explanation is a grammatical error. If words are being randomly switched half the time, it seems pretty likely that happened here.

“Of course!” We say with hindsight, “the word embedding will learn to encode gender in a consistent way. In fact, there’s probably a gender dimension. Same thing for singular vs plural. It’s easy to find these trivial relationships!”

It turns out, though, that much more sophisticated relationships are also encoded in this way. It seems almost miraculous!

Relationship pairs in a word embedding. From Mikolov et al. (2013b).

It’s important to appreciate that all of these properties of \(W\) are side effects. We didn’t try to have similar words be close together. We didn’t try to have analogies encoded with difference vectors. All we tried to do was perform a simple task, like predicting whether a sentence was valid. These properties more or less popped out of the optimization process.

This seems to be a great strength of neural networks: they learn better ways to represent data, automatically. Representing data well, in turn, seems to be essential to success at many machine learning problems. Word embeddings are just a particularly striking example of learning a representation.

Shared RepresentationsThe properties of word embeddings are certainly interesting, but can we do anything useful with them? Besides predicting silly things, like whether a 5-gram is ‘valid’?

\(W\) and \(F\) learn to perform task A. Later, \(G\) can learn to perform B based on \(W\).

We learned the word embedding in order to do well on a simple task, but based on the nice properties we’ve observed in word embeddings, you may suspect that they could be generally useful in NLP tasks. In fact, word representations like these are extremely important:

The use of word representations… has become a key “secret sauce” for the success of many NLP systems in recent years, across tasks including named entity recognition, part-of-speech tagging, parsing, and semantic role labeling. (Luong et al. (2013) )

This general tactic – learning a good representation on a task A and then using it on a task B – is one of the major tricks in the Deep Learning toolbox. It goes by different names depending on the details: pretraining, transfer learning, and multi-task learning. One of the great strengths of this approach is that it allows the representation to learn from more than one kind of data.

There’s a counterpart to this trick. Instead of learning a way to represent one kind of data and using it to perform multiple kinds of tasks, we can learn a way to map multiple kinds of data into a single representation!

One nice example of this is a bilingual word-embedding, produced in Socher et al. (2013a). We can learn to embed words from two different languages in a single, shared space. In this case, we learn to embed English and Mandarin Chinese words in the same space.

We train two word embeddings, \(W_

Of course, we observe that the words we knew had similar meanings end up close together. Since we optimized for that, it’s not surprising. More interesting is that words we didn’t know were translations end up close together.

In light of our previous experiences with word embeddings, this may not seem too surprising. Word embeddings pull similar words together, so if an English and Chinese word we know to mean similar things are near each other, their synonyms will also end up near each other. We also know that things like gender differences tend to end up being represented with a constant difference vector. It seems like forcing enough points to line up should force these difference vectors to be the same in both the English and Chinese embeddings. A result of this would be that if we know that two male versions of words translate to each other, we should also get the female words to translate to each other.

Intuitively, it feels a bit like the two languages have a similar ‘shape’ and that by forcing them to line up at different points, they overlap and other points get pulled into the right positions.

t-SNE visualization of the bilingual word embedding. Green is Chinese, Yellow is English. (Socher et al. (2013a) )

In bilingual word embeddings, we learn a shared representation for two very similar kinds of data. But we can also learn to embed very different kinds of data in the same space.

Recently, deep learning has begun exploring models that embed images and words in a single representation. 5

The basic idea is that one classifies images by outputting a vector in a word embedding. Images of dogs are mapped near the “dog” word vector. Images of horses are mapped near the “horse” vector. Images of automobiles near the “automobile” vector. And so on.

The interesting part is what happens when you test the model on new classes of images. For example, if the model wasn’t trained to classify cats – that is, to map them near the “cat” vector – what happens when we try to classify images of cats?

(Socher et al. (2013b) )

It turns out that the network is able to handle these new classes of images quite reasonably. Images of cats aren’t mapped to random points in the word embedding space. Instead, they tend to be mapped to the general vicinity of the “dog” vector, and, in fact, close to the “cat” vector. Similarly, the truck images end up relatively close to the “truck” vector, which is near the related “automobile” vector.

(Socher et al. (2013b) )

This was done by members of the Stanford group with only 8 known classes (and 2 unknown classes). The results are already quite impressive. But with so few known classes, there are very few points to interpolate the relationship between images and semantic space off of.

The Google group did a much larger version – instead of 8 categories, they used 1,000 – around the same time (Frome et al. (2013) ) and has followed up with a new variation (Norouzi et al. (2014) ). Both are based on a very powerful image classification model (from Krizehvsky et al. (2012) ), but embed images into the word embedding space in different ways.

The results are impressive. While they may not get images of unknown classes to the precise vector representing that class, they are able to get to the right neighborhood. So, if you ask it to classify images of unknown classes and the classes are fairly different, it can distinguish between the different classes.

Even though I’ve never seen a Aesculapian snake or an Armadillo before, if you show me a picture of one and a picture of the other, I can tell you which is which because I have a general idea of what sort of animal is associated with each word. These networks can accomplish the same thing.

(These results all exploit a sort of “these words are similar” reasoning. But it seems like much stronger results should be possible based on relationships between words. In our word embedding space, there is a consistent difference vector between male and female version of words. Similarly, in image space, there are consistent features distinguishing between male and female. Beards, mustaches, and baldness are all strong, highly visible indicators of being male. Breasts and, less reliably, long hair, makeup and jewelery, are obvious indicators of being female. 6 Even if you’ve never seen a king before, if the queen, determined to be such by the presence of a crown, suddenly has a beard, it’s pretty reasonable to give the male version.)

Shared embeddings are an extremely exciting area of research and drive at why the representation focused perspective of deep learning is so compelling.

Recursive Neural NetworksWe began our discussion of word embeddings with the following network:

Modular Network that learns word embeddings (From Bottou (2011) )

The above diagram represents a modular network, \(R(W(w_1),

W(w_5))\). It is built from two modules, \(W\) and \(R\). This approach, of building neural networks from smaller neural network “modules” that can be composed together, is not very wide spread. It has, however, been very successful in NLP.

Models like the above are powerful, but they have an unfortunate limitation: they can only have a fixed number of inputs.

We can overcome this by adding an association module, \(A\). which will take two word or phrase representations and merge them.

By merging sequences of words, \(A\) takes us from representing words to representing phrases or even representing whole sentences. And because we can merge together different numbers of words, we don’t have to have a fixed number of inputs.

It doesn’t necessarily make sense to merge together words in a sentence linearly. If one considers the phrase “the cat sat on the mat”, it can naturally be bracketed into segments: “((the cat) (sat (on (the mat))))”. We can apply \(A\) based on this bracketing:

These models are often called “recursive neural networks” because one often has the output of a module go into a module of the same type. They are also sometimes called “tree-structured neural networks.”

Recursive neural networks have had significant successes in a number of NLP tasks. For example, Socher et al. (2013c) uses a recursive neural network to predict sentence sentiment:

One major goal has been to create a reversible sentence representation, a representation that one can reconstruct an actual sentence from, with roughly the same meaning. For example, we can try to introduce a disassociation module, \(D\). that tries to undo \(A\) :

If we could accomplish such a thing, it would be an extremely powerful tool. For example, we could try to make a bilingual sentence representation and use it for translation.

Unfortunately, this turns out to be very difficult. Very very difficult. And given the tremendous promise, there are lots of people working on it.

Recently, Cho et al. (2014) have made some progress on representing phrases, with a model that can encode English phrases and decode them in French. Look at the phrase representations it learns!